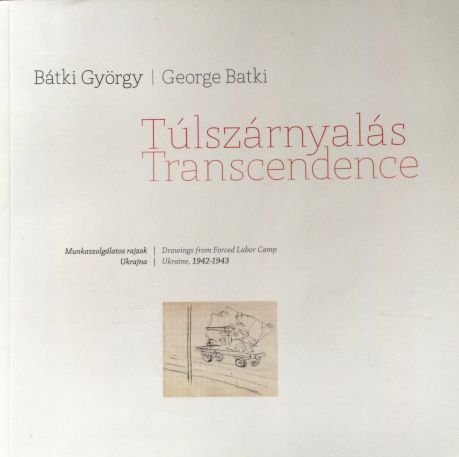

Transcendence: Drawings from a forced labor camp. Ukraine, 1942-43

2B Galéria, Budapest

George Batki (April 17, 1912 - September 7, 2005)

July 8, 2014 throughAugust 18, 2014

The Batki family migrated to Syracuse, NY in November 1957, after the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. The following description, written by George Batki’s son, John Batki, elucidates the background for George Batki’s diaries.

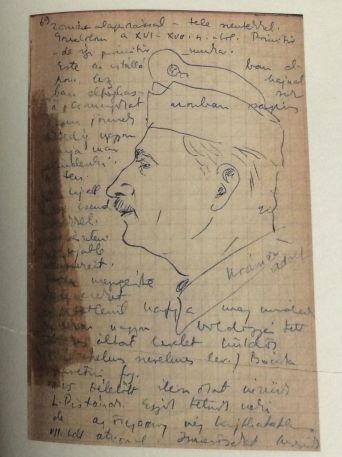

During the Second World War (1939-1945), George Batki, along with other Jewish Hungarian men, was conscripted into the Hungarian Army Labor Service. He was called up three times: from July to December 1940, in Hungary; May 1942 to September 1943, in the Ukraine; and finally from May 1944 until his liberation in November 1944, in northeast Hungary. His surviving diary, written and drawn into a small pocket notebook, dates from May 13 to September 24, 1942. It is a record of the first four months spent in the Ukraine by Special Labor Company 107/2. A friendly Hungarian soldier on home leave delivered it to Margaret Batki in Miskolc. (A second diary, the sequel to this surviving diary, was confiscated by a sergeant during a subsequent search.)

When he was called up in May 1942, George Batki was thirty years old and had been married for five months. His wife, Margaret, was pregnant; the baby was expected in December. The diary was actually intended as a long letter to Margaret. For obvious reasons, the text and drawings provide a “self-censored” image of the forced labor camp. In lieu of a litany of the heaviest events, the pain and suffering, the reader receives a relatively positive and optimistic depiction of everyday life, fueled by love and hope. The drawings present all of the “local participants”: fellow forced laborers, Hungarian army guards and officers, Ruthenian sappers, an Italian lieutenant, a Russian prisoner of war, and many Ukrainian villagers, men and women, old and young alike—“Heads from the Ukraine,” as the artist described them on the flyleaf of another surviving sketchbook. The “cast” is gone, but the written and drawn lines remain and carry on testifying. As George Batki wrote in a later afterword for this dairy, by making his diary accessible to all, he “intended to create a humble monument to the many friends and companions who perished.” As are demonstrated by his subsequently written reminiscences, included in the exhibition catalog, as well as his entire luminous life, the murderous age of hatred known as the Holocaust can be transcended by remembrance and patient love.

Syracuse, New York, April 2014

© ALMA 2014